By Sachie Mizohata

Introduction

Nippon Kaigi (NK, the “Japan Conference”) is Japan’s largest and most powerful conservative right-wing organization, whose members include current Prime Minister Abe Shinzō and most of his Cabinet.1 This nationalist non-party political group was relatively unknown until recently. A surge in publication and media attention of late, however, has made this arcane society suddenly visible, particularly in regard to its influence on politics, nationalist agenda, and revisionist causes. Many recent publications2 associate Nippon Kaigi with Japan’s rightward leaning trends: political climate, leadership, and a new current of nationalist sentiment. They report that NK agendas are essentially aligned with Abe’s political ambitions and views, most notably constitutional revision. As the 2016 Upper House election results strengthened their ability to shape Japan’s political agenda, Nippon Kaigi merits concern and scrutiny. NK adherents profess to promote Japan’s prosperity and international prestige, to restore Japan’s national pride and unify the country. These goals seem honorable and appealing to many Japanese. Nonetheless, since NK supporters are uncritical in their affirmation of the imperial past and suppression of civil liberties, they may achieve the opposite results. Herein lies their contradictions and paradoxes.

In this paper, I first provide an overview of Nippon Kaigi and its emerging background. The next section examines NK’s vision of a ‘proud’ nation. The third section reviews key elements of NK’s ideology. A final section examines their contradictions.

What is Nippon Kaigi?

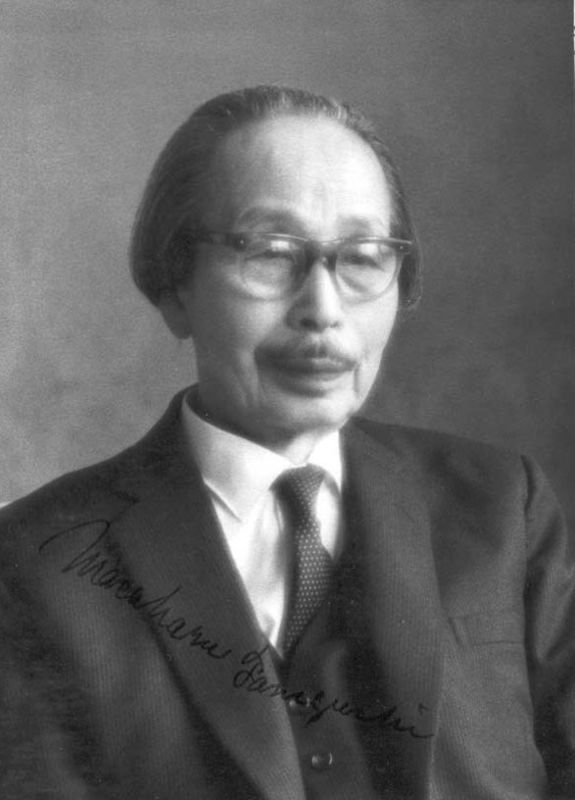

Nippon Kaigi’s ideological foundations and legitimacy are rooted in two major religious movements in early 20th century Japan. One is Seicho no ie 生長の家 (literally House of Birth and Growth), a syncretic religious organization founded by Taniguchi Masaharu in 1930. The other one is Jinja Honchō 神社本庁, the Association of Shinto Shrines, an administrative organization organized in 1946 that oversees some 80,000 Shinto shrines.3

|

Seicho no ie |

Jinja Honchō |

Nippon Kaigi was established in 1997 through integration of two existing groups. One was Nihon o mamoru kai (Society for the Protection of Japan) founded in 1974. The other was Nihon o mamoru kokumin kaigi (People’s Conference/National Conference to Protect Japan) founded in 1981).

Nihon o mamoru kai, originally a union of Shinto and Buddhist religious organizations, rallied under the banner of anti-communist and opposition to the Buddhist Soka Gakkai, which they branded a threat to Japanese society. This is ironic since New Komeito (an arm of Soka Gakkai) is an indispensible coalition partner of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).4

Nihon o mamoru kokumin kaigi originally consisted of rightist cultural luminaries, business leaders, and imperial army veterans. They were keen on making the emperor again the head of state and implementing constitutional changes, education reforms, and a strengthened defense posture, which coincide with present Nippon Kaigi objectives.5

|

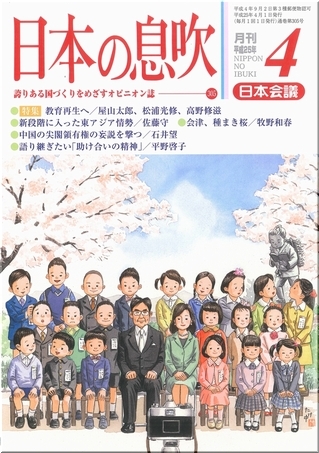

Today Nippon Kaigi has approximately 38,000 members. Its monthly magazine, Nippon no ibuki (Breath/Vigor of the Nation) deals extensively with denouncing criticism of the Nanking Massacre as historical fabrication or the Tokyo Trial as victor’s justice and illegitimate. NK has 47 chapters in all prefectures, which are further divided into some 240 local chapters. Although lacking a strong membership base, their outsize influence rests on direct connections with lawmakers: the Parliamentary League for Nippon Kaigi (Kokkai giin kondankai) of 280 members (PM Abe as a special advisor to it; Inada Tomomi, Defense Minister; Koike Yuriko, former Defense Minister and present Tokyo governor) as well as its Local Assembly Union (Nippon Kaigi chihō giin renmei) with 1,692 members.6 In other words, “Nippon Kaigi has backroom clout … and a network that reaches deep into the political establishment.”7

At present, NK’s president is Takubo Tadae, professor emeritus at Kyorin University, who has succeeded Miyoshi Tōru, the third NK president (2001 ― 2015) and former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. In practice, secretary-general Kabashima Yūzō is at the helm. Other key members include a spectrum of professionals from business such as former chairperson of Bridgestone Tire to conservative academics, public figures, and Japan Medical Association Chairperson. In addition, given its religious roots, it is worth mentioning that 24 out of 62 NK representatives are from religious organizations.8

|

Miyoshi Tōru’s “Tennō Heika Banzai (Long live the Emperor)” charge at Meiji Jingu Kaikan on National Foundation Day on February 11, 2016. |

Active NK supporters in academia figure prominently in the debate over reinterpreting Japan’s pacifist constitution. In summer of 2015, the role of NK academics became obvious when tens of thousands of people protested against the security legislation. While the overwhelming majority of legal scholars and practitioners condemned the “war bills” as unconstitutional, Cabinet Secretary Suga Yoshihide claimed during the Diet discussion that many constitutional scholars supported the bills. Having been urged to mention such proponents to support the position, Suga lamely cited three scholars: Nagao Kazuhiro of Chuo University, Nishi Osamu of Komazawa University, and Momochi Akira of Nihon University. All three are Nippon Kaigi members.9 More tellingly, these professors are also the members of the two offshoots set up by the NK: Utsukushii Nihon no Kenpō o Tsukuru Kokumin no Kai (National Society to Create a Constitution for a Beautiful Japan; hereafter, the Kenpō group) as well as 21 Seiki no Nihon to Kenpō Yūshikisha Kaigi (Association of Experts on the Constitution for 21st Century Japan). We observe an intensification of the lobbying capacity of NK through a multiplication of groups and associations.10

The authors of recent publications note that NK’s strength resides with formidable skills and sustained grassroots efforts for mass organizing to mobilize people and resources. They hold lectures and rallies to pressure local assemblies to submit resolutions to Tokyo by bombarding them with requests, petitions, and phone calls. NK predecessors pushed through the law recognizing the national anthem and flag as Japan’s national symbols in 1999. Then, NK collected about 4 million signatures calling for reform of the Fundamental Law of Education (Kyoiku kihon hō), which in turn was enacted in 2006 in Abe’s first stint as Prime Minister.11 Furthermore, NK has unceasingly pressured, through various local and national groups, against initiatives on gender-free education, sex education in schools, and gender equality in political participation, while promoting traditional family values, gender norms, and women’s primary roles as mothers and wives at home.12

These activities illustrate NK’s values. They fulminated against bills proposed by the Democratic Party of Japan as ‘four bad laws,’ which included 1) legalizing suffrage for foreign permanent residents, 2) women using their maiden names after marriage, 3) a national Human Rights Protection Bill (Jinken yōgo hōan), and 4) the right of a woman to accede to the emperorship.13 NK launched a successful counter-campaign of signature collection against each of these. Overall, its political activities and documents reveal not only their ultra-conservative and inward-looking nature, but also their anathema to the left and malaise with women ― except like-minded colleagues.

In short, NK has strong influence on leading decision-making bodies. They aim at promoting constitutional changes and traditional education and values.

What are NK’s Objectives?

The above unveils NK’s uncommon capacity to lobby and push forward bills and laws that have deep impact on the daily life of the Japanese. The NK website14 describes six organizational objectives:

1.A beautiful tradition of the national character for Japan’s future

(美しい伝統の国柄を明日の日本へ)

2. A new constitution suitable for the new era

(新しい時代にふさわしい新憲法を)

3. Politics that protect the country’s reputation and the people’s lives

(国の名誉と国民の命を守る政治を)

4. Creating education that fosters Japanese sensibility

(日本の感性をはぐくむ教育の創造を)

5. Contributing to world peace by enhancing national security

(国の安全を高め世界への平和貢献を)

6. Friendship with the world tied up with a spirit of co-existence and co-prosperity

(共生共栄の心でむずぶ世界との友好を)

The lengthy description of their objectives can be summed up in the following points: 1) Promote worship of the imperial household at the heart of our state and people, whose imperial lineage can be traced over 125 generations of unbroken descent (back to origins of the sun goddess). 2) Eliminate the occupiers-drafted constitution and accompanying problems that inhibit the independent will of the state to protect its security and turning national defense over to a foreign power. NK therefore seeks to amend the constitution to fully utilize the Self-Defense Forces. 3) Restore a politics that emphasizes the importance of national interests, reputation, and sovereignty, including paying homage to Japan’s war dead at Yasukuni shrine. 4) Nurture young people to cultivate patriotic spirit, respect for the national anthem, flag, and history, and cherish quintessential Japaneseness. 5) Bolster defense forces in order to effectively assume global leadership and counterbalance threats posed by China and North Korea. 6) Finally, build friendly relations with other countries through exchange programs. In short, their overarching concerns are to promote a narrow state-centric notion of prosperity and well being. Stated differently, they are unconcerned about the welfare of ordinary Japanese.

|

Aum Shinrikyo facility for manufacturing sarin, Satyan 7, Yamanashi Prefecture, 1995 |

Particularly notable is NK’s longing for national pride and traditional virtues, as noted in their reiteration of pride and tradition. Why so? A good way to understand them may be looking at their historical background, starting two years prior to NK’s founding year; it was “the year of the Kobe earthquake and Aum Shinrikyo’s deadly gas attacks on Japan’s subway. … The two events … had a profound impact on the nation’s confidence.”15 Especially, the latter generated a vague sense of national drift and moral decay. Meanwhile, the LDP’s single-party rule shifted to LDP-led coalition governments. In the post-bubble recession, persistent economic crises deepened and conditions that supported reliance on the premier power (the U.S.) weakened, reinforced by population aging, overseas relocations of Japanese firms in tandem with the rise of China and globalization.16

At that time, the war generation which experienced war first-hand was aging and disappearing. It made up 75% of the population in 1950, and was reduced to roughly 23% by 2000.17 By then, Emperor Shōwa, distant reminder of the lost war, was long gone. Norma Field notes an undercurrent of revisionism: “Hirohito missed his moment for saying ‘I’m sorry,’” leaving a legacy of still unresolved problems, and “a responsibility [of ordinary Japanese citizens] whose continued denial has been translated into silent acquiescence to the harsh discipline required by [country rebuilding and] economic success.”18 Muto Ichiyo thus stresses: “In this fashion, a vessel was created to preserve and nurture the idea that the wartime actions of the empire were not wrong, and even that they were right.”19

In this milieu, the political climate for Japan’s wartime deeds had changed. Gavan McCormack delineates:

Beginning in the 1990s, the official Japanese stance on its past changed. After four decades in which the past was set aside, … as the Cold War crumbled and affluence palled, the problem of reconciliation with the region began to be faced. … As part of this burgeoning international pressure on Japan, … dozens of law suits demanding apologies and compensation have been lodged with Tokyo district courts on behalf of former ‘comfort women’ and the many other victims of Japan’s colonialism and aggression.20

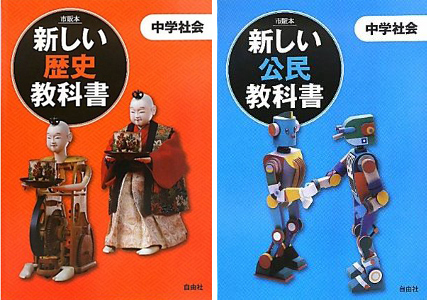

This conversely attests to the maturation of human rights discourse, especially in the form of global feminism, as well as the gradual decline of US hegemony in the post-Cold War political context. Moreover, 1995 marked the Murayama Statement in which the Prime Minister delivered an official apology to neighboring countries. Humiliated by “apology diplomacy”, NK forerunners gathered 5.2 million signatures opposing the landmark statement.21 1996 saw the formation of the NK affiliated group, Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform (新しい歴史教科書をつくる会) led by Nishio Kanji, Fujioka Nobukatsu, and others to remove or downplay critical descriptions of Japan’s war conduct. Their action accorded with official textbook treatments: “the Japanese system exercises control primarily through state screening.”22

|

Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform textbooks |

Japan’s selective memory came under increasing international censure. As Akiko Hashimoto shows, such war reflections, identity politics, and scrutiny engendered or unraveled a sequence of emotions in the course of Japan’s postwar ‘long defeat.’ Hashimoto eloquently depicts “the desire to repair a damaged reputation” to create a positive national identity.23 Kato Norihiro points out that words such as “pride” were seldom used in the public sphere when Japan enjoyed quiet confidence, gained by economic boom and pro-American peace diplomacy under Article 9. Kato thus sees Japan’s growing anxiety, malaise, and shaken confidence as leading to the emergence of Nippon Kaigi: “In reality it is akin to Japan’s version of the Tea Party: Like the Tea Party in the United States, it is a product of deep conservative anxieties about the future. … Both Nippon Kaigi and the Tea Party cast themselves as ‘grassroots’ movements that represent ‘traditional’ values of ‘the people.’ One Tea Party slogan is ‘Take Back America,’ and in the last election one L.D.P. slogan was ‘Take Back Japan.’”24 In Kato’s view, there are two ways to rehabilitate national identity to restore honor to Japan. One viable way is to face the past wrongdoings. Another is to repudiate them and to forge or project a sense of pride in national belonging through cover-ups and self-adulatory slogans.25 The two precisely oppose each other. NK chiefly adopts the latter (in a futile attempt) to change the national memory and to reclaim a positive Japanese identity.

Furthermore, according to historian Yamazaki Masahiro, NK has two outstanding goals. One is to restore Yasukuni’s national status, and another is to alter the constitution.26 As for the latter, NK established the Kenpō group in 2014 with local chapters across the country. NK launched a campaign to collect 10 million signatures for constitutional revision. In 2015, it held a national rally at the Nippon Budōkan Hall, where PM Abe sent a congratulatory video reaffirming his pledge to revise a constitution suitable for the 21st century.27

In sum, NK’s emergence coincided with a moment in the 1990s when the postwar legacy of problems intensified in the historical context of the rise of international criticism and international anger over memory of colonialism and war. This took the form of reactions to Japan’s international apologies, textbook debates, the maturation of human rights discourses, decline of the war generation, and was accentuated by Japan’s economic downturn. In parallel, revisionist discourse, impervious to pressures for a shared history with neighboring countries, grew powerful as did state leaders holding such views.

NK’S Ideological Foundations

Recall that both Nihon o mamoru kai and Nihon o mamoru kokumin kaigi share the same word to name their groups: “mamoru” (to defend, protect, preserve, or safeguard). The word conveys their concern that something at stake was being lost.

|

Taniguchi Masaharu |

If Nippon Kaigi hopes to revive or “reclaim” past glory by rewriting history and revising the constitution ― what are the ideological sources for their legitimacy and justification? NK has two major religious components; the first is Seicho no ie, from which many of NK’s key figures originally came. The founder of this syncretic religious organization, Taniguchi, embraced the idea of kokutai (national polity) ― the central plank to worship the emperor as a divine ruler, and to see Japan as the center of the world and the Yamato race as superior to other races, which in turn could justify imperial ventures abroad in the name of national defense. He proclaimed that the postwar constitution was the root of all evils and called for the revival of the prewar Meiji Constitution. As a war sympathizer, Taniguchi was barred from public service in the postwar era before restarting Seicho no ie in 1949 championing two major issues: anti-communism and emperor veneration.28 In 1964, Seicho no ie established its political wing called Seicho no ie seiji rengō (active until 1983) and its student wing Seicho no ie gakuseikai zenkoku sōrengō in 1966 (Seigakuren, Confederation of National Student Associations). Seicho no ie withdrew from the political arena in 1983. Subsequently, having shifted from its anti-leftist-nationalist approach of the past to focus on ecology issues, it publicly criticized the Abe administration before the 2016 Upper House election and declared that it would not to support it.29

One of the student adherents of the early Seicho no ie was NK’s secretary-general Kabashima who built a right-wing movement at Nagasaki University in the late 1960s with his senior leader Andō Iwao, and subsequently established a rightist organization Nihon seinen kyōgikai in 1977 (Japan Youth Council). The Nihon seinen kyōgikai developed into a secretariat of the Nippon Kaigi and is presently the nucleus of NK. Kabashima is also the chairman of the Nihon Seinen Kyōgikai, whose headquarters is located in the same building as NK. Its goal of constitutional reform was inscribed in the April 2015 issue of the Seinen Kyōgikai magazine, Sokoku to seinen (Fatherland and youth). The organization affirmed its pledge for constitutional amendment and promoted the campaign in light of the results of the last parliamentary election.30

Another founding father of Nippon Kaigi is Murakami Masakuni, Liberal Democratic Party veteran, and heavyweight.31 As a leader of both of forerunner organizations, Murakami worked as a bridge to the political world for the Nihon Seinen Kyōgikai and played a crucial role in the formation and development of NK. Nowadays, however, Murakami openly criticizes the Abe administration and its underhanded dealing with the state secrecy law, security laws and constitutional changes. NK deliberately avoids discussing its agenda before each election. With the focus of election campaigns placed on the economy, NK’s issues are deliberately played obfuscated. However, with its electoral victory in hand, the ruling coalition claims public endorsement for these contentious issues and rams through the Diet unpopular laws. His criticism implies the existence of other dissidents inside NK.

Initial members of NK include at least three more men from the former Seigakuren. One is Momochi Akira, as discussed earlier with regard to the security legislation. Takahashi Shirō of Meisei University is former deputy chairman of the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform and a revisionist scholar whom the Japanese government sent to UNESCO meetings to oppose incorporating Nanjing Massacre-related materials in the Memory of the World Register list. Ito Tetsuo is the head of the Japan Policy Institute, a rightist think tank known as Abe’s brain trust for nationalistic policies. The above three were involved with Seicho no ie in combatting the leftist student movement in the 1960s-70s, and all are members of Nippon Kaigi’s policy committee.32 Another Seigakuren person, Eto Seiichi, has served to bridge NK and Abe’s LDP.33 Eto is a Nippon Kaigi backer and Special Advisor to the Prime Minister. He is Abe’s long-term political associate who supported his drive for a rare second term in office, which Miyoshi Tōru calls one of NK’s great achievements.34

|

Inada Tomomi |

In addition to older male sympathizers, there are female Seicho no ie-related NK sympathizers. Inada Tomomi, who is viewed as a strong contender for the LDP presidency, shows her old copy of Taniguchi Masaharu’s Seimei no jissō (Truth of Life) in a meeting (the video is available in Japanese).35 She recalls that the book was given by her grandmother and her parents who were avid readers of it. Inada herself belongs to Taniguchi Masaharu Sensei o manabu kai (the Association to Learn About Taniguchi Masaharu Sensei, led by Nakajima Shoji), whose members advocate Taniguchi’s fundamentalist views.

This association is related to the management of Tsukamoto Kindergarten in Osaka which emphasizes cultivation of patriotism and respect for the national flag and national anthem. In 2015, Madam Abe Akie was appointed as honorary principal.36 The principal is NK’s representative in Osaka, and its associated elementary school is to open next year.37 As shown in the video below, children sing Japanese martial songs after they chant aloud the Imperial Rescript on Education (Kyōiku Chokugo): the imperial moral foundation between 1890 and 1946.38 The Rescript officially adopted the idea of kokutai, Shinto as the state religion (State Shinto), in short Shinto ultra-nationalism. This not only reflects their key goal but approach for indoctrinating young people in love for the nation, pride, and dedication to public ends, which have been subverted, in their reading, by the postwar education system.

The June 1998 issue of Nippon no Ibuki argues that Japan needs to ‘rectify’ the educational system, which is distorted by the supremacy of test scores and educational qualifications, ‘excessive’ focus on human rights, ‘excessive’ individualism, a masochistic view of history, and strong biases supportive of Nikkyōso (Japan Teachers Union), which have resulted in anti-Japanese ideology in schools.39 Thus far, we have noted three central organizations; the Nihon seinen kyōgikai, Japan Policy Institute, and Taniguchi Sensei o manabu kai, all associated with NK. These key members of Seicho no ie-related groups have played seminal roles.

|

Tsukamoto kindergarten group recitation highlighting nationalist and imperial themes |

Besides Seicho no Ie, another important religious organization is Jinja Honchō: “one of Japan’s most successful political lobbies.”40 Although the name conveys the impression that it is a public institution, it is in fact a private institution. Jinja Honchō was established in February 1946, very soon after the abolition of the Jingiin (Institute of Divinities) due to the Shinto Directive issued by GHQ (General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander for the Allies Powers) to prevent the use of Shinto for political purposes. Jingiin was formally incorporated into the state bureaucracy under the aegis of the Home Ministry, which administered governmental sponsorship, perpetuation, and dissemination of State Shinto. Jingiin evaded war responsibility as a non-military entity, despite having the lead in propagating ultra-nationalistic ideology and promoting the war. Under provisions guaranteeing freedom of religion, Jinja Honchō was formed by then religious leaders to take over some of the functions of the Jingiin. This means that, although it did not enjoy the same privileges as before, it was able to restore its prewar religious order and revitalize its ideology privately.41

The Jinja Honchō had long sought to reinstitute the calendar system based on the emperor’s reign, the gengō prewar calendar having been proscribed by the GHQ which saw it as a vehicle for reassuring imperial authority. With Seicho no ie, Nihon Seinen Kyōgikai, Shinto Seiji Renmei and others, Jinja Honchō founded Gengō Hōseika Kokumin Kaigi (People’s Conference/National Conference to Implement the Gengō Legislation), the forerunner of Nihon o mamoru kokumin kaigi, in 1978.42 Soon its goal became a reality; “in 1979, Japan’s conservative government ensured that the emperor-centered calendar would continue by passing legislation that mandated continued use of the gengō practice.”43 To date the gengō has been continuously used by public agencies.

Today Jinja Honchō has a political wing, which is called Shinto Seiji Renmei (神道政治連盟Shinto Association of Spiritual Leadership). In 2016, during the New Year holidays, shrines provided advertisements for constitutional revisions at the request of Jinja Honchō that responded to the movement of the abovementioned Kenpō group.44 After the 2016 reshuffle of the Abe administration, 19 out of the 20-member Cabinet are members of the Shinto Seiji Renmei, while 14 are members of Nippon Kaigi.45 Therefore, in other words, the political elements and Shinto-inspired elements have been yoked together to compose the Abe government. Note that Jinja Honchō’s president is Tanaka Tsunekiyo, a representative of the Kenpō group and one of NK’s vice-presidents.

In addition to Jinja Honchō, NK boasts affiliations with many Shinto and other religious organizations,46 though not limited to faith-based organizations (e.g., Nihon Jyosei no Kai or Association of Japanese Women that advocates traditionalist causes). These groups with arguably irreconcilable differences of religion co-exist and collaborate under the same NK organizational umbrella. In NK’s view, this may be seen as “a coexistence of deities without conflicts” in accord with Japanese “national spirit” to respect harmony, as underscored in their goal statement.47 Certainly, this arrangement of different groups yoked together blurs the separation between its religious and political institutions, which also link to NK’s goal to ease “the excessive separation of religion and state.”

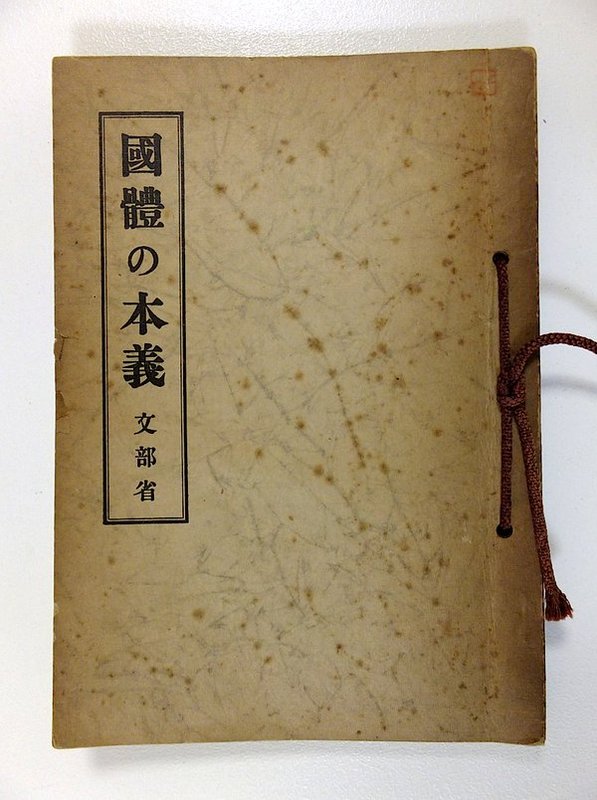

While reading NK documents, we take note of their understanding of “tradition”. According to Shimazono Susumu, professor in religious studies, the Japanese tradition cited by the Nippon Kaigi is primarily equated with the concept of kokutai, which denotes “the ideology of bansei ikkei (‘ten thousand generations in a single line’)”48, the allegedly unbroken line of imperial rulers, plus notions of Japan as a uniquely incomparable country, and the supremacy of the Yamato race. Shimazono contends that unbroken history without rupture, albeit mythological, is important to them as demonstrative of imperial continuity and sacerdotal majesty.49

|

Kokutai no Hongi |

Yamazaki argues that NK’s ideology is well articulated in two treatises: Kokutai no Hongi (Fundamentals of the National Polity) and Shinmin no Michi (The Way of the Subject), issued by the Ministry of Education in 1937 and 1941 respectively. As for the first manifesto, he uncovers NK’s ideological links between these documents and its goal statement; the discredited wartime terms and rhetoric are replaced with equivalent words. The kokutai (国体) is replaced with kunigara (国柄), and banpōmuhi (万邦無比) with sekaini rui o minai (世界に類を見ない) ‘without parallel in the world.’50 As for The Way of the Subject, it explained how Japanese imperial subjects were expected to see “who they were ― or should aspire to be ― as a people, nation, and race.”51 These moral virtues included prioritizing the spirit of harmony, self-sacrifice, and devotion to the public good, which are found in a draft constitution compiled by the LDP.

Both manifestos relate to the wartime slogan “‘Hakko Ichiu,’ which literally means putting all the eight corners of the world under one roof.”52 Or more simply: the world as a single family under Japanese control. The result is to wrongly applaud Japan as a liberator of Asia from Western colonialism. Thus NK members refer to World War II as the Great East Asia War, supposedly viewing themselves as spiritual successors of the prewar government.53

Concerning NK’s official ideology and its effort to “defend”, “protects”, or “preserve” the tradition, Muto Ichiyo summarizes:

The premise is that something has been lost. What is it? It is the essence of the Empire of Japan. To Abe, the ‘postwar’ has been an extremely unfortunate era. The reason is that the honor of the glorious Japanese empire was denied and the Occupation imposed the constitution on Japan. It is not only Abe who thinks this way; this thinking is fairly deeply rooted in postwar Japanese leadership long dominated by the LDP. In fact it is my contention that in the postwar Japanese state, the continuity of the Japanese empire was preserved, if surreptitiously, as a principle of the legitimacy of the state.54

Postwar Japan started in effect with the Imperial Rescript on Surrender, as outlined by Herbert P. Bix: “a masterpiece of propaganda packed with terms like “preservation of the national polity,” “subjects of the empire,” and the “indestructibility of the divine land.”55 The essence of imperial rule is the persistence of antiquated apparatus, tools, and inherited patterns of thinking in the NK: recycling the kokutai and myths, suggesting Japanese uniqueness, self-deluding superiority56 (e.g., recent boom in books and TV shows), patriotic exhortation, pristine singular identity,57 reinstatement of State Shinto58 to restore imperial divine sovereignty and its legitimacy. This means, in NK’s view, there has been no conclusive rupture with the past, except for war-renouncing Article 9 ― a constant reminder of Japan’s defeat. That’s why it is of utmost importance for them to regain belligerency as the state’s lost sovereign right to reclaim Japan’s unbroken history.

We have reviewed the major claims of NK. Significantly, some NK members are associated with members of Zaitokukai and participants in xenophobic hate speech rallies directed at Japan’s Korean population (Zainichi), which contain disturbing rhetoric and incite hostility towards disadvantaged groups.59 Nippon Kaigi seeks to return Japan to greatness, by repurposing imperial essence, military powers, Shinto, and tradition ― in a quest for imperial continuity. These gaps between NK’s goals for a beautiful Japan and its offensive mindset and strategies give rise to major contradictions.

NK’s Contradictions

NK expresses hope to build a great and ‘proud’ nation. Although NK members have not reached consensus on what parts and how to amend the constitution, we examine three issues which the Japan Policy Institute (run by a Special Advisor to PM) identifies as priorities and the contradictions to which they give rise: 1) Article 9; 2) the provision on emergencies in time of crisis; and 3) Article 24 on family values. (For a comprehensive study, see Lawrence Repeta’s work: Japan’s Democracy at Risk ― The LDP’s Ten Most Dangerous Proposals for Constitutional Change http://apjjf.org/2013/11/28/Lawrence-Repeta/3969/article.html .)

Article 9

NK routinely dismisses the postwar constitution as a humiliating reminder of Japan’s defeat and an American imposition. NK’s Miyoshi Japan’s national security is jeopardized by war-renouncing Article 9, which unfairly prevents Japan from achieving the necessary conditions for a sovereign state. PM Abe also insists on adherence to a ‘proactive pacifism’ that would enable Japan to become a “normal country”, by which he means that the Self-Defense Forces (SDF) would be a full-fledged National Army so as to protect against territorial threats by bolstering the U.S.-Japan alliance at home and abroad.

The right to collective self-defense is, however, a two-edged sword. Miyazaki Reiichi, a former Director-General of the Cabinet Legislative Bureau, argues that a state’s inherent right to individual self-defense is clearly distinct from the right to collective self-defense, as the latter constitutes the right to assist and defend an ally under attack, even if Japan is not attacked. Miyazaki thus thinks that it would clearly go against Article 9.60 Moreover, Magosaki Ukeru, a former foreign ministry official, argues that the new security legislature makes no contribution to Japan’s defense or regional stability. Instead, it rather heightens regional tensions and increases the risk of increased conflict, bringing back disturbing echoes of its imperial past to neighboring countries. It also allows the U.S. to make extensive use of Japan’s SDF to assist it in its costly military operations, a process likely to increase Japan’s military subordination.61

Retrospectively, these views have proven accurate62 in light of the Prime Minister’s promise concerning the security legislature at the U.S. Congress on April 29, 2015 to be enacted in the summer, even before the bills were brought up for deliberation in the Diet. Similarly, The Stars and Stripes on May 13 of 2015 reported that the 2016 U.S. defense budget was drawn up in anticipation of Japan’s passage of the military expansion bills.63 As John W. Dower concludes, “Japan will have no choice but to become a participant in America’s global military policies and practices, even where these may prove to be unwise and even reckless.”64 Abe’s embrace of two allies’ partnership only deepens Japan’s servility as a U.S. client state, which is incompatible with the interests of national security and economic prosperity that the NK incumbents wish to pursue to rebuild a ‘proud’ country capable of global leadership. Similarly, rightists wish to place the U.S.-Japan relationship on an equal footing, contradicting their complacency about the U.S.-Japan alliance, particularly the U.S. military presence in Japan and the unequal Status of Forces Agreement between Japan the United States.

NK members stick to the traditional security discourse that narrowly focuses on the safety of the state. Put differently, they virtually ignore a multitude of other threats to human security, and thus fail to get security priorities right. Moreover, they simply ignore civil society initiatives as a basic alternative to military solutions when managing conflicts when discussing threats posed by other countries. During the Upper House Budget Committee session October 5, 2016, Defense Minister Inada (also a NK member) claimed that military budgets take precedence over child welfare while calling for doubling military investment. She stated: “If we use the money earmarked for child-care benefits to increase the defense budget [given limited financial resources], Japan’s military spending will come close to the international standards.”65

By contrast, Amartya Sen contends that security is ultimately a people-centered matter, hence “national security” is merely “one component of human security.”66 “Human security means protecting fundamental freedoms … It means protecting people from critical (severe) and pervasive (widespread) threats and situations.”67 Sen notes that, “sometimes national security in the political context seems like a barrier rather than a component to fostering human security. But at the same time, when we consider reducing the budget for national security, we also have to think of the other implications. There’s no reason why there should be a conflict between the two.”68

In effect, we impose social costs thanks to misplaced security priorities. Japan’s important national security issues certainly include its worsening inequalities and poverty in recent years. As for the latter, roughly one out in six Japanese people live beneath the poverty line, wherein households earn less than half the median income (1.22 million yen in 2012).69 This makes Japan’s poverty rate fourth highest among the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) member countries, and Japan’s child poverty rate is even higher. This is at odds with Japan’s declared commitment to human security, which the Prime Minister recognized in his speech at Harvard’s Kennedy School in 2015.70 As boasted, Japan embarked on the initiative on human security to demand protection from various insecurities, which was co-chaired by Sadako Ogata and Amartya Sen under the Commission in 2003 within the United Nations framework. Therefore, NK’s narrative on protection of the country rings hollow, due to its narrow conception of state security as well as the NK-dominant government’s lack of commitment to improving human security.

An Emergency Clause Against Human Freedoms and Human Rights

The second elements that NK claims to change are constitutional democracy and individual freedoms. The constitution drafted by the LDP grants many new powers to the government in the event of emergencies, if so declared by the PM, to suspend ordinary constitutional processes. Simultaneously, it deletes the principles of popular sovereignty and the universality of human rights, and specifies that the exercise of individual freedoms and rights shall not violate ‘the public interest and public order’, in any ways this might be interpreted by the authorities (cf. the Meiji Constitution: “Freedom of speech, writing, press, assembly, and association were now guaranteed only ‘to the extent that they do not conflict with the public peace and order’”71). If deemed as infringement, the government can hence restrict speech, press, and expression. Moreover, in compensation for freedoms and rights, the draft constitution invokes much more the individuals’ duties to the state, such as respect for the national flag and anthem, defending the country stoutly, upholding the new constitution, etc.72 Overall, NK members see democracy, human rights, and individual freedoms as Western notions, which are therefore irrelevant to Japanese characteristics and values. To them, these imported or imposed notions have to be replaced by a Japanese-specific social order and traditional priorities, grounded in the imperial institution, thereby putting national interest above individuals’ rights.73

Needless to say, the individual’s right is enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, irrespective of citizenship or culture. NK’s advocacy of limiting substantive freedoms that people enjoy, runs counter to international efforts to expand freedoms that are set out in the UN guiding principles. Specifically, it is the very opposite of human development, i.e. a shared vision of the United Nation agencies and countries, incarnated by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The UNDP defines human development as enlarging people’s freedoms or “reducing the unfreedoms and insecurities of various kinds that plague human lives.”74 This notion has been fruitfully developed by Mahbub ul Haq and Amartya Sen.75

Sen provides two major reasons to explain why freedom is so valuable, by citing two distinct yet partially overlapping contents of freedom: opportunity freedom and process freedom. He argues:

First, more freedom gives us more opportunity to pursue our objectives ― those things that we value. It helps, for example, in our ability to decide to live as we would like and to promote the ends that we may want to advance. … Second, we may attach importance to the process of choice itself (emphasis in the original). We may, for example, want to make sure that we are not being forced into some state because of constraints imposed by others (emphasis added).”76

Today’s Japan tramples on both types of freedoms, and thus suffers from democratic deficits. The deprivation of basic opportunity freedom refers to widespread impoverishment (lack of freedom to achieve well-being), as discussed above. Process freedom refers to access to information, public participation in decision-making, transparency as well as free speech and media freedom. As mentioned above, NK’s Murakami severely criticizes the fact that new legislation was forced through the Diet over strong public opposition, while the present government obfuscated the issues at stake. On top of that, Japan’s press freedom ranking has declined sharply in recent years. In the 2010 Reporters Without Borders index, Japan (under the Hatoyama administration) ranked 11 out of 178 countries. In the 2016 index, the country ranked 72 out of 180 countries. These facts reflect deficiencies in assuring both opportunity and process freedoms by a government that represents the will of people.77 In short, NK’s advocacy of scaling back civil liberties would expose Japan to domestic criticism as well as international scrutiny over universal norms and values of democratic freedoms, human rights, and the rule of law.78 Concomitantly, this would undermine the goal of securing a respected place for Japan’s standing in the world community (cf. Japan as claimant to a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council).

Article 24 and Anti-Women Bias

Finally, NK is keen to limit women’s freedoms and human rights. Sugano Tamotsu, whose book titled Nippon Kaigi no Kenkyu (Research into Japan Conference) has been a recent best-seller, points out that NK’s focus is mainly on issues of “women and children” (e.g., anti-gender equality, against woman as Empress, not to mention anti-abortion views since the earlier Taniguchi’s epoch).

This leads us to look at NK’s underlying biases against women. They attribute today’s family-related problems (e.g. family instability) to the postwar constitution. They assert that Article 24, which affirms conjugal equality, individual choice, and mutual consent for marriage, has a noxious influence on families due to such Western individualistic nature of marriage and personhood.79 To them, proponents of keeping separate surnames for married couples wish to dissolve marriage and family; thus, they believe that there should be a legal definition of the family to be safeguarded. (This means that their definition of the nature of the family would consequently determine the related concepts of gendered-roles within the households, marriage, and personhood of the wider society.) Since they define the ideal ‘Japanese family’ as three generation households with ancestral lineage and family ties, they wish to revert from the nuclear family to traditional family norms.

NK’s model fits the LDP’s long-held vision of “a Japanese welfare society”, which gives continuing priority to economic growth over families and social protections, consigning women to family care.80 This reflects the LDP draft, which extols and obligates traditional family values. The LDP proposed Preamble states: “The Japanese people take pride in their country and land…. they also respect harmony and form a nation where families and the whole society mutually support each other.” Higuchi Yōichi, leading authority on constitutional law, argues that the wordings of “land”, “harmony”, “support”, and “family” carry legal significance and weight within Japan’s history. For the war generation, “support” evokes wartime systems of neighborhood mutual group for mandatory help and watch for the possible infractions of laws; “harmony” means subservience to the interests of the state, and “the family” stands for male-domination to revoke gender equality.81 And, no doubt such family spirit, filial obedience, and hierarchy are a metaphor for the imperial power structure.

NK’s idealized role of family is akin to the Meiji’s Civil Code on the legal regulations of marriage and kinship, enforcing obligations of domestic duties, gender divisions, etc. Such familial ideal is suggestive of the ié, the patriarchal family system, which traditionally privileged the family head and subjected women to servitude to the ié. NK’s notion reinforces patriarchal primacy to produce offspring to preserve blood lines, which is closely associated with their male-preference-primogeniture in family arrangements: male-only imperial succession.82 NK’s belief in hewing to the tradition of male emperors, however, proves simply false since there were formidable female emperors in Japan’s early history.

|

Establishment of “office for the encouragement of building a society in which all women shine,” 2014 |

Moreover, NK’s willful disregard of equality between women and men is in opposition to international conventions and remedial actions for gender equality (e.g., the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women – CEDAW). NK’s obsolete traditional model of family fails to keep up with women’s diverse lifestyles, families, and work styles, and does not accommodate them with viable options. On the contrary, women are roundly penalized in various forms if they do not comply with or fit the NK/LDP model of family functioning and of women’s roles. Consider the facts that “about 1 in 3 women in Japan aged between 20 and 64 who live alone are living in poverty.”83 54.6% of single parent/lone adult (overwhelmingly mothers) households containing one or more children is considered poor, living on less than half of median income.84 Note, too, the gender disparity found in the womenomics initiative to promote women’s advancement and empowerment in the business world under Abenomics. In the Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office, there is not a single woman in the photo of “a group of male leaders who will create a society in which women shine.”85 It will be difficult to build a proud and prosperous nation without overcoming Japan’s deep-seated sexism and addressing women’s adversities (e.g. the very small percentage of women in the Japanese parliament86).

In sum, NK is fraught with contradictions and theoretical incoherence. Interestingly, as noted above, certain basic discrepancies have emerged between the Abe administration and NK owing to their different emphasis and priorities. Above all, NK’s reactionary efforts run counter to international efforts and international commitments to human rights including women’s rights.

Conclusions

Nippon Kaigi is embedded in Japan’s officialdom, and its influence is re-directed to mainstream political activities under Abe’s stewardship. NK efforts go hand in hand with government intervention in education, declining investigative journalism, readjustment and glorification of the imperial past, nationalistic sentiments, military buildup, unilateral decisions, impositions, and initiatives at the expense of human welfare and human development.87 Still, their efforts also include reconciling contradictions which, I think, emanate from the Janus-faced nature of their identity in handling various issues: actions/practices as opposed to intentions, separate messages for domestic and international audiences, etc. (e.g., pacifist narrative versus their opposite insular stance toward neighboring countries and affirmation of imperial Japan; different views about the role of the emperor: “the emperor on the one hand and the United States on the other, the inner and outer axes of national identity.” 88) In short, NK’s revisionist practices expose problems and contradictions.

Related articles

1. David McNeill, Nippon Kaigi and the Radical Conservative Project to Take Back Japan http://apjjf.org/-David-McNeill/4409.

2. Hayashi Keita and Sato Kei, Japan’s Largest Rightwing Organization: An Introduction to Nippon Kaigi http://apjjf.org/-Mine-Masahiro/4410

3. Muto Ichiyo, Retaking Japan: The Abe Administration’s Campaign to Overturn the Postwar Constitution http://apjjf.org/2016/13/Muto.html

Notes

Recently published books include: 1) Nippon Kaigi no Kenkyu by Sugano Tamotsu, 2) Nippon Kaigi no Zenbou by Tawara Yoshifumi, 3) Nippon Kaigi to Jinja Honchō by Narusawa Muneo (ed), 4) Nippon Kaigi by Yamazaki Masahiro, and 5) Nippon Kaigi no Shotai by Aoki Osamu.

Sugano, 2016; Yamazaki, 2016, pp. 66-67.

Yamazaki, 2016, p. 68.

Yamazaki, 2016, p. 28.

Sugano, 2016; Yamazaki 2016.

Some observers are dismissive of Nippon Kaigi describing it as devoid of outstanding talent and resources. (At the same time, they underline its influence on politics.) Sugano Tamotsu notes that NK is built on a handful of influential nationalists. For instance, joint representatives of Utsukushii Nihon no Kenpō o Tsukuru Kokumin no Kai (National Society to Create a Constitution for a Beautiful Japan) are Sakurai Yoshiko, Takubo Tadae, Miyoshi Tōru, etc. Sakurai and Takubo serve as representatives of the Japan Institute for National Fundamentals. Many officers of the affiliated organization overlap those of NK.

It made it compulsory to teach “love of country” as part of school curricula, and incorporate teaching guidelines about the national anthem and flag, moral virtues, respect for the emperor, mythology, national territories and waters, importance of the Self-Defense Forces, and so on. See Sugano, 2016.

Yamaguchi, Tomomi. 2016. “Nippon Kaigi no target no hitotsu wa kenpō 24jyō no kaiaku” in Nippon Kaigi to Jinja Honchō, Tokyo: Shukan kinyōbi, pp. 172-183.

See Kato, Norihiro. 2015. Sengo Nyūmon. Tokyo: Chikuma shinsho.

Kato. 2015. Sengo Nyūmon. pp. 514-515.

Field, Norma. 1993. In the Realm of a Dying Emperor. New York: Vintage Books, pp. 201-202.

Hashimoto, Akiko. 2015. The Long Defeat. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 5.

Kato, Norihiro. 2015. Sengo Nyūmon. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, p. 433.

Yamazaki, 2016, p. 89.

Sugano, 2016; Yamazaki 2016.

Sugano, 2016, p. 85.

Sugano, 2016, Yamazaki, 2016.

See Sugano, 2016.

Shimazono, Susumu and Yamazaki Masahiro. “Nippon Kaigi to Shūkyō Nationalism” in Kotoba, summer 2016, p. 139.

The Rescript requested that people as “loyal subjects” of “Our Emperor” should be “filial to your parents,” “as husbands and wives be harmonious,” and “furthermore, advance the public good and promote common interests; always respect the Constitution and observe the law; should emergency arise, offer yourselves courageously to the State; and thus guard and maintain the prosperity of Our Imperial Throne coeval with heaven and earth.” See here

See the June 1998 issue of Nippon no ibuki, p. 11, which was quoted by Yamazaki, 2016, pp. 139-140 here.

Shimazono, Susumu and Yamazaki Masahiro. “Nippon Kaigi to Shūkyō Nationalism” in Kotoba, summer 2016, pp. 142-143. Yamazaki, 2016, pp. 72-74.

Its founder was former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Ishida Kazuto. See Yamazaki, 2016.

Dower, John. 1993. Japan in War and Peace. New York: New Press, p. 2.

Kataoka, Nobuyuki. 2016. “Jinja no nottori jiken” in Nippon Kaigi to Jinja Honchō, Tokyo: Shukan kinyōbi, p. 141.

Such groups include Yasukuni Shrine, Ise Shrine, Reiyūkai (霊友会 Spiritual-Friendship Association), Sūkyō Mahikari (崇教真光), Makuya of Christ (キリストの幕屋), Gedatsu-kai (解脱会), The Institute of Moralogy (モラロジー研究所), Rinri Kenkyūshō (倫理研究所, Institute for Ethics or Ethics Study Group), and the like.

Dower, John. 1999.Embracing Defeat. New York: New Press, p. 307.

Shimazono, Susumu. 2016. “Jinja to kokka no kankeiwa dō henka shitaka” in Nippon Kaigi to Jinja Honchō, Tokyo: Shukan kinyōbi, p. 121.

Yamazaki, 2016, p. 127.

Dower, John. 1999.War Without Mercy. New York: Pantheon Books, p. 24.

Yamazaki, 2016, pp. 164-165.

For instance, Yasukuni pilgrimage, tour to Ise Shrine on the occasion of the G7 in 2016.

Sugano, 2016.

Miyazaki, Reiichi. 2014. “Kenpō 9 jo to shūdanteki jieiken wa ryōritsu dekinai,” Sekai, August. Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, pp. 148-154.

See Magosaki’s interview by Iwakami Yasumi: here; Magosaki Ukeru and John Junkerman, Japan’s Collective Self-Defense and American Strategic Policy: Everything Starts from the US-Japan Alliance here

See McCormack, Gavan: here; Recently, for example, large SDF transport helicopters have been carrying construction equipment into the planned site of the U.S. military helipad in Takae, Okinawa. See here

Dower, John. Embracing Defeat. p. 381.

See the Japanese videos: here and here 1) Inada Tomomi: “I think that such politics placing the people’s life first is wrong.” 2) Former Minister of Justice, Nagase Jinen: “The people’s sovereignty, basic human rights, and pacifism ― these three are the postwar regime itself imposed by MacArthur on Japan, therefore we have to get rid of them to make the constitution on our own.” Their brazen remarks make clear their disinterest in achieving social improvement and prosperity for the public.

Sen, Amartya. 2005. “Principal Voices,” in TIME magazine, November 21, p. 13.

Sen, Amartya. 2009. The Idea of Justice. Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, p. 228.

Yamaguchi, Tomomi. 2016. “Nippon Kaigi no target no hitotsu wa kenpō 24jyō no kaiaku” in Nippon Kaigi to Jinja Honchō, Tokyo: Shukan kinyōbi, pp. 172-183.

See Osawa, Mari. 2011. Social Security in Contemporary Japan. New York: Routledge / University of Tokyo Series

For example, see Fukushima Mizuho’s work on marriage and family.